Wisconsin Native Women and Culture Honored Through Art

.entry-date::after {content: ” by Val Niehaus”;}

December 1, 2016 – Full Issue

Honoring elders of the community is of great importance to the Forest County Potawatomi culture and tribe. It is taught to the children starting at a young age, and it is reinforced throughout their childhood. Always listen to the elders as they are wise and knowledgeable when it comes to the Potawatomi people and their past.

PTT had the privilege of visiting the Center of Visual Arts (CVA) in Wausau, Wis., to visit an exhibit titled “Ancestral Women: Elders from Wisconsin’s 12 Tribes”. This is a collection of portrait weavings by Mary Burns honoring Native women from the Wisconsin tribes.

Burns is an award-winning jacquard weaver/artist from northern Wisconsin who has her own studio, Manitowish River Studio, located in Mercer, Wis. Burns has loved the art of weaving since her high school art class, and this passion has grown into what is now her life. Not only has she displayed her work in many exhibits and festivals, but she also teaches tapestry and other forms of weaving as well as felting. Burns is a person who connects with nature, people, and her surroundings to help inspire her love of weaving.

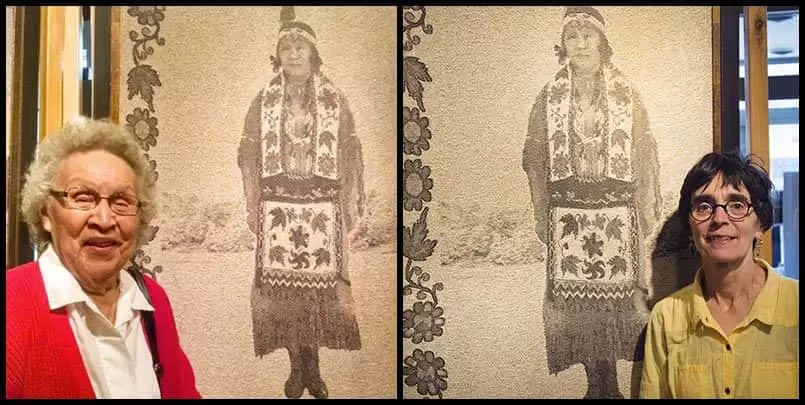

One of the most rewarding reasons to visit this exhibit is that it showcases Native women from Wisconsin’s 12 tribes (11 are federally-recognized; the Brothertown Nation is seeking federal status). Another is that the Potawatomi woman featured in one of the artworks is someone that many in this area are related to or have heard about while growing up. This woman is Mary “Waseyan” Waubiness George, who is Arlene Alloway’s mother.

The following is taken from the booklet one receives when visiting the exhibit:

Mary Waubiness, whose Indian name was Waseyan, meaning “first light rays of the day,” was born on August 20, 1910, to Bemsek and Charles Waubiness of McCord Indian Village. She had an elder brother named Mtegwab, meaning “bow.” Mary and Mtegwab were both fluent speakers of the Potawatomi language.

Waseyan attended Pipestone Indian Training School in Pipestone, Minnesota, which opened in 1893 and closed in 1953. Aside from academics, she learned a variety of other life skills including sewing, gardening, cooking and nursing.

In 1927, she married Isaac George (Gawsat) and had one child, a daughter named Arlene. Waseyan was a community contributor in foster parenting and she passed on her learned skills to younger ladies. She also served as a midwife, delivering many babies when called upon.

She began her spirit journey on March 16, 1984, and in June of the same year, her husband followed her.

Waseyan’s devotion to her community, her knowledge of traditional skills, and her work as a midwife were important threads that rooted her in place. For her portrait, Burns highlighted Waseyan’s oral beadwork on her traditional regalia by drawing out the patterns and laying them in as a border.

PTT had the chance to sit down with Arlene Alloway and ask about her thoughts in seeing her mother being portrayed in this art exhibit.

Alloway said, “I was very touched to see this photo of my mother. The regalia that my mother was wearing in this photo was made by her own hands. This was just one of many pieces she made herself.”

Alloway was also asked about what she thought of the artist who made this weaving. “Words can’t describe the fine work she does. I thank her very much for doing this weaving of my mother.” This was all said with a huge smile on Alloway’s face which showed how much she appreciated seeing her mother honored in this special way.

The inspiration behind Burns’ work and the reason for the extensive labor, love and commitment she devoted to creating this display was expressed when she explained, “I felt that women were not being honored over time. I really wanted to create an exhibit where women were the focus, and in thinking of women in this area, it was only natural and the correct choice to start with the Native people. So, I had actually started with this (she points to the portrait of Emma Pettibone of the Ho-Chunk Nation), and I didn’t have the idea for this exhibit when I started weaving this piece. But when I saw this photo by H.H. Bennett of Emma Pettibone, I was mesmerized by her. She seems very regal, and I love that she had this beautiful appliqué. From there, the whole idea just came to me and then we started going to the different tribes to see who they wanted honored in this exhibit.”

Along with these beautiful portraits that Burns crafted, she also did six clan weavings: bear, eagle, loon, marten, crane and turtle; and four weavings that incorporate the culture of Native people. These demonstrated special activities and important events including maple sugaring, building a birch bark canoe, harvesting wild rice, and one of a sunrise which symbolizes a new day and thankfulness for living.

It is difficult to summarize this art exhibit in words as one must see it oneself to appreciate how truly impressive it is. One must see the texture and size of these portraits with one’s own eyes. One must see and feel the expressions that Burns has captured from the photos she was given to transform into an artwork of woven fabric. Every single one is absolutely remarkable in its craftsmanship and represents an incredible work of art.

When asked about future pieces, Burns said she wants to stay with the Native women. Perhaps we will be seeing another Potawatomi woman honored as Mary “Waseyan” Waubiness was with her likeness preserved forever in an exquisite work of art.